Safflower is a complex dye plant. It contains red and yellow dyes, and they bind to different fibers.

Safflower (Carthamus tinctorius) is one the oldest domesticated plansts. It arose in present-day Syria more than 5000 years ago from a cross between 2 or 3 wild species from the genus Carthamus (this is known from studies where DNA from safflower is compared with DNA from the wild plants).

Safflower quickly spread to an area that stretches from ancient Egypt to Japan. The plant, and its dye, has been found in several Egyptian graves – e.g. garlands from around 1400 BC and safflower dyed textile from around 1800 BC.

Safflower is also mentioned in several ancient texts – from Mesopotamian cuneiform tablets to the works of Aristoteles and the Talmud (Jewish texts from the first centuries AD). Apart from mentioning safflower as a dye plant, the Talmud also gives quite a detailed account of its aphrodisiac effect!

Like so many other ideas and goods, safflower traveled the Silk Road to China, where its use began about 2000 years ago. In fact, it became such a success that the Emperor had to outlaw it by a 1292 decree – the food supply was falling too much.

The plant has two uses: as a dye, and as an oil crop (the seeds can be pressed for oil). This puts the plant in good company with other very old domesticated plants such as flax (Linum usitatissimum) for textile and oil, and hemp (Cannabis sativa) for textile, rope, and medicinal (or ritual) use.

For dyeing, only the safflower petals are used. They are harvested by pulling them off the large, globular flower every second or third day during flowering. Each round does not give much of a harvest, and the plant can really prick your fingers, but over time, the petals add up to a nice little harvest. In the experiments described below, I did use bought material, since I don’t have much of my own harvest.

Dyeing with safflower is somewhat complicated, and really one of those cases where you ask yourself how people came up with such a procedure in antiquity.

The problem is that safflower contains several different dyes. Most of them are yellow: a mixture of yellow compounds that are nothing like the yellows a natural dyer will normally prefer, coming from plants like weld and tansy. The yellows of those plants are flavonoids, and they are considered the best natural yellow dyes. The yellows in safflower are of a type called C-glycosylchalcones, but that probably doesn’t tell most people much!

But the yellow dyes in safflower are soluble in water, so when the petals are just soaked in water for an hour, lots and lots of yellow will come out.

The yellows from safflower can be used to dye wool. The picture below shows safflower yellow on 10% alum mordanted wool – but I really don’t recommend using that dye. Yellow is always a problem in natural dyeing, being the least lightfast color, but there are much better options than safflower, like tansy, birch, and weld.

The first step in dyeing with safflower is to soak the petals in plenty of water for an hour, then strain out the petals and discard the water. Then, rinse with several shifts of water. Some recipes say to keep going until the water runs clear, but I couldn’t get it to do that… it would require many shifts of water!

In addition to the yellow dyes, safflower contains a red dye called carthamin. The special thing about carhamin is that it is not soluble in water at neutral pH, only in base (high pH).

I have tried extracting the red color by first soaking 20 g of safflower petals and discarding several shifts of yellow. Then, I put the petals in fresh water and added drops of a sodium carbonate solution until pH was 11, so quite a strong base. I left it at room temperature for a couple of hours (but according to Jenny Dean in Wild Colous, 1 hour would be enough).

The photo below gives a glimpse of what is going on. The bowl on the left contains safflower petals and water. The petals are a fresh orange, and there is yellow dye in the water. In the bowl on the right, I’ve added base. The liquid is still more or less the same yellow, but the petals have lost their clear orange color and look a bit worn out. That is because the carthamin has been dissolved.

Once the carthamin has been dissolved, the petals are discarded. Before dyeing with the liquid, it should be neutralized. I added acetic acid until pH was about 6, so close to neutral. I dyed a silk scarf and some cotton cloth by just leaving the textiles in the dye bath overnight, stirring a couple of times. The textile weighed about 20 g, so textile and dyestuff are at a 1:1 ratio.

The result:

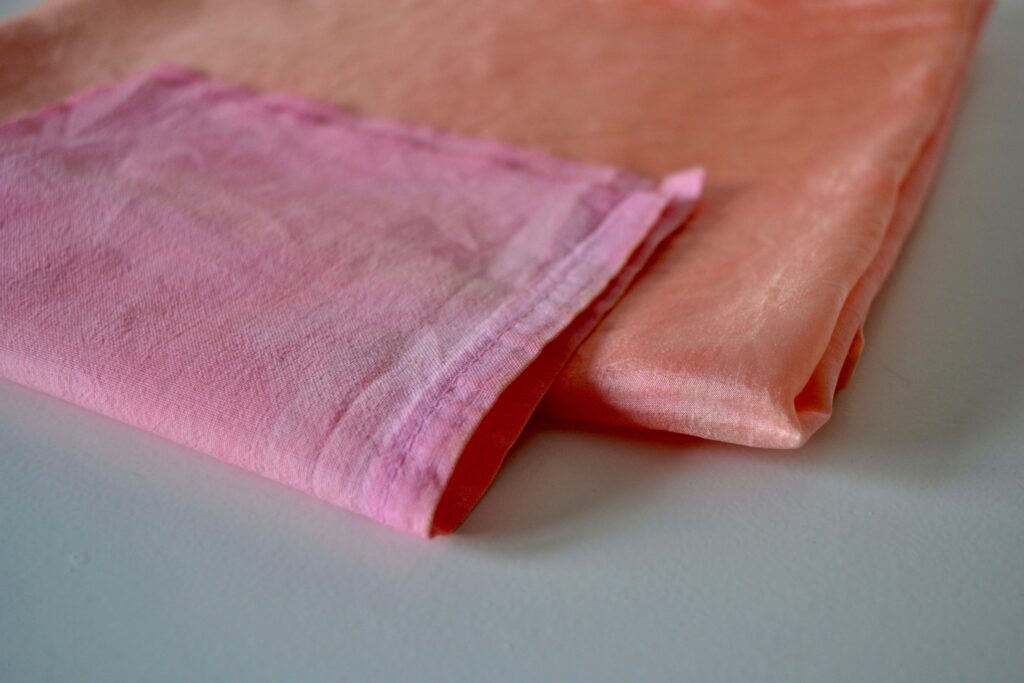

The cotton is pink, but the silk is more of a coral or salmon color. The problem is that both red carthamin and yellow dyes can bind to silk, while only carthamin binds to cotton.

When pink silk is the goal, the solution (according to Dean) is first dyeing cotton, then removing the dye from the cotton and dyeing the silk with it. The cotton dye step acts as a purification of the dye, since cotton only binds the red dye.

I’ve tested the complicated method, of course! Soaked 20 g of safflower petals, removed as much yellow as possible, dissolved carthamin with base and neutralized the bath, then dyed a piece of cotton by leaving it in the dyebath overnight. The color was about the same as the cotton in the picture above.

Then, I put the pink cotton in fresh water, shown in picture 1 below. I added sodium carbonate to pH 11 and left it overnight. The result is shown in picture 2. The color has been stripped off the cotton, which is now looking rather pale, and the liquid looks orange. I removed the cotton, neutralized the liquid, and added a silk scarf that I left in the dye overnight. Picture 3 shows what it looked like the next day: the silk has turned pink, and only little dye is left in the dyebath.

Once the silk was dry, the color was much paler, of course. Below, the two-step dye is on the right, and the one-step dye from before is on the left.

The color intensity is obviously quite different although both scarves weigh 20 g and were dyed using 20 g of safflower petals. But the color is also different. The scarf on the right, where the dye was purified by binding it to cotton, is a pure pink, while the color of the left scarf has a yellow component.

So the purification of the dye, by binding it to cotton, stripping it off, then dyeing silk, it does work. But a lot of dye is lost on the way. That’s not such a big surprisem seeing that some color is left in the cotton, and some is left behind in each dye bath.

The two-step silk pink is not a very efficient dyeing method, and the huge areas used for safflower cultivation make sense. Stronger colors will need quite large amounts of dyestuff, and the yield is really quite modest when cultivating this plant.

So, some may ask why safflower was even used for pink on such a scale. Why didn’t people just use cochineal? The answer is quite simple. In safflower’s heyday, China before 1292, for example, there was no contact between the New and Old World. Cochineal use didn’t spread to Europe before the 1540’s. Before that, other insect reds were used (kermes, lac, Polish cochineal) but they were extremely expensive and only for the true elite, just think of Henry VIII’s kermes dyed Cap of Maintenance.

Today, safflower cultivation is increasing, but for oil production, not dye. The seed is often found in wild bird seed mix, too. But the plant makes sense in any dye garden, I think.

Of course for dyeing – the safflower pink color does not have a very good light fastness, but it is the only red plant dye that will bind to plant fibers, and it binds without any mordants or heating.

Safflower is also a beautiful flower. It is good for drying, and is said to be very durable when dried. Last year, I just left mine in the garden, and they were extremely decorative throughout the winter. The picture below is from my dye garden in November of last year, the safflower shapes turning into skeletons.

I am growing safflower again this year in my dye garden. It usually springs right out of the ground when sown directly after all risk of frost has passed, between May 20th and the end of June.

Astrids butik is my shop for all the products connected to Midgaards Have – dyes, yarn for dyeing, seeds – and all the products connected to my other project, Retrofutura plus a growing range of other yarns and knitting design.